Three Louisiana pension funds invested a combined $100

million in 2008 in Fletcher Asset Management. Each of the three funds invested

from 3.9 percent to 8.6 percent of their assets in Fletcher's scheme after the

firm made a pitch promising to deliver every investor's dream: high returns

with low risk.

In fact, the arrangement promised a guaranteed 12 percent

return on their money. If the return dipped lower, the difference supposedly would

be made up by $50 million put up by a third-party investor.

This week, the Trustee in Fletcher’s bankruptcy said the value

of the assets in Fletcher were worth less than $8 million. Fletcher had valued

the fund at $352 million.

It’s hard to have sympathy for public pension officials who

are gullible enough to fall for a high guaranteed rate of return. The Municipal Employees' Retirement

System of Louisiana actually had no policy on credit risk or interest rate risk

– fundamental risks that should have been assessed before investing.

Despite

this naïve approach to managing public funds, the pension officials should have

been able to depend on the auditors to ferret out any wrong-doing on the part

of Fletcher Asset Management. Unfortunately, the auditor team failed again to

properly carry out its audit responsibilities and as such, failed to alert the

public to the significant short-comings in Fletcher’s financial statements.

Based on

the Trustee’s investigation, investors were victims of a fraud defined by:

- the extensive use of wildly inflated valuations,

- the existence of fictitious assets under management,

- the improper payment of excessive fees,

- the misuse of investor money,

- and efforts wrongly to deny the Louisiana Pension Funds a key benefit of their investment agreement – mandatory redemption of their investment under certain circumstances.

The

Funds were also victims of an environment where self-interest all too often

trumped fiduciary obligations.[1]

The

Trustee went on to say,

“Auditors,

too, failed to exercise adequate professional skepticism when reviewing

valuations; failed to insist on adequate disclosure of related party

transactions involving [Alphonse Fletcher] and his family, Citco, and

Unternaehrer; and failed to require disclosure of redemption obligations which

would have caused a collapse of the Funds.”[2]

There were numerous red flags

that ought to have been readily apparent to the administrators and auditors for

the Funds. These red flags included:

- Manager-controlled pricing of customized investments, supported by a valuation agent lacking adequate experience and independence;

- Massive subscriptions into the Funds in November and December 2008 (following the collapse of Lehman Brothers) from the FAM-controlled Richcourt Funds, when both the administrator and auditor knew that the Richcourt Funds had suspended net asset values (“NAVs”) and redemptions and imposed gating on investors;

- Repeated massive sudden gains in multiple investment positions;

- Multiple transactions in major positions at values that were inconsistent with the mark-to-model valuations;

- Valuation reports that did not meet minimum industry standards;

- Guaranteed minimum investor returns for certain investors;

- Absence of any down months over 127 months from June 1997 through December 2007;

- Fund complexity;

- Lack of timely issuance of annual audited financial statements;

- Lack of timely reporting and communications to investors, including delays in receiving monthly and weekly financial data from the investment manager in order to calculate NAVs; Backdating corporate and transaction documents;

- Ascribing value to non-exercised contract rights to buy securities without actually investing in them;

- Mismatch between the terms of the investment vehicle and the underlying investments; and

- Continued inflows and outflow over short time periods from affiliates and related entities.

These red flags should have

caused the administrators and auditors to have investigated, disclosed and

stopped. None did.[3]

The Trustee identified a number of auditing standards that

were not complied with by the auditors. The Trustee said,

“To

arrive at their opinions and discharge their duties, Grant Thornton and Eisner

were required to plan and perform their audits in accordance with generally

accepted auditing standards (GAAS). These standards prescribe the minimum

threshold conduct for an auditor. The Trustee reviewed, among other evidence,

the accountants’ work papers and deposition testimony, and concluded that the

audits performed failed to comply with GAAS. Grant Thornton and Eisner failed

to qualify their audit opinions appropriately to acknowledge that the financial

statements were materially misstated and should not have been relied on by

those receiving them. In this regard, it is important to remember that the audience for

these audits was not only the Funds, but also the investors to whom the various

audits were addressed.

Grant

Thornton or Eisner (or both) violated the following GAAS:

• General Standard No. 1,

which requires the auditor to “have adequate technical training and proficiency

to perform the audit.”

• General Standard No. 2,

which requires the auditor to “maintain independence in mental attitude in all

matters relating to the audit.”

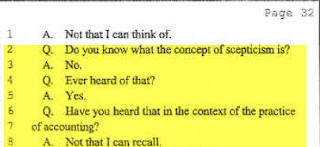

•

General Standard No. 3, which requires the auditor to “exercise due

professional care in the performance of the audit and the preparation of the report.” Due professional care requires the auditor to exercise

professional skepticism. Professional skepticism is an attitude that includes a

questioning mind and a critical assessment of audit evidence.

• Standard of Field Work No.

3, which requires the auditor to “obtain appropriate audit evidence by

performing audit procedures to afford a reasonable basis for an opinion

regarding the financial statements.”

• Standard of Reporting No. 1,

which requires the auditor to state whether the “financial statements are

presented in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP).”

•

Standards of Reporting No. 3, which requires that “when the auditor determines

that the informative disclosures are inadequate, the auditor must state so in

the auditor’s report.”

I’ll examine these in more

detail in future blogs.

style="display:inline-block;width:728px;height:90px"

data-ad-client="ca-pub-0906764851584171"

data-ad-slot="8133153944">

[1] Page

4, Trustee’s Report and Disclosure Statement, Fletcher International, LTD.,

Issued 11/25/13, Case No. 12-12796 (REG). US Bankruptcy Court Southern District

of New York

[2]

Ibid. Page 8

[3]

Ibid. Page 10